If you collected comics in the 1990s, or you’ve ever dug through dollar bins and wondered why there are so many hyper-violent women in metal bikinis staring daggers at you, you’ve already brushed up against the bad girl comics origin story, whether you realized it or not.

Bad Girl comics weren’t just “sexy female characters.” They were a specific, market-driven trend that exploded during the 1990s superhero comics boom. They had a look. They had a tone. They had a business model. And they were inseparable from the direct market, the speculator era, and the rise of independent publishers chasing lightning in a bottle.

This guide isn’t academic. It’s not hand-wringy. And it’s not here to apologize for the 90s. The goal is simple: explain where Bad Girl comics came from, why they dominated shelves for a few years, how they shaped what came after, and, most importantly for collectors, how to recognize the ones that still matter today.

Because while most 90’s bad girl comics are common as dirt, some first appearances, early printings, and low-distribution books absolutely deserve more respect than they get.

First, let’s define the term properly, because this is where most discussions go wrong.

Bad Girl comics refer to a distinct 1990s genre trend, not a blanket label for any female character in revealing clothing. The Bad Girl boom describes a wave of comics—primarily from the early to mid-1990s—featuring violent, often supernatural female leads, exaggerated anatomy, provocative costumes, and a heavy cheesecake aesthetic, usually blended with horror or dark fantasy.

Key traits of 90s Bad Girl comics:

These comics didn’t just appear randomly. They were a product of timing.

By the early 1990s, the comics industry was in full expansion mode. The success of Image Comics, chromium covers, polybags, and “#1 issue culture” created an environment where bold visuals sold better than nuanced storytelling. Shops were ordering deep. Collectors were buying multiples. Publishers were chasing what sold fast.

Bad Girl comics were perfect for that moment.

They were instantly readable from the cover alone. You didn’t need continuity knowledge. You didn’t need a deep emotional hook. You needed a striking female figure, a sharp logo, and a promise of violence or sex, or ideally both.

And for a few years, it worked.

To understand the origin of the bad girl genre, you have to go further back than the 1990s. Way further.

The term “Bad Girl” is a deliberate inversion of Good Girl Art, a style that dates back to the 1930s and 1940s. Good Girl Art featured wholesome, pin-up-inspired women in lighthearted or suggestive, but not overtly sexual, situations. Think calendar art, war-time illustrations, and early pulp covers.

Good Girl Art was flirtatious. Bad Girl Art was confrontational.

By the time the term “Bad Girl” was being used in comics circles, it implied more than just sex appeal. It meant danger. Aggression. Autonomy. Women who were not passive objects but active threats.

The shift didn’t happen overnight. It evolved gradually:

The important thing to understand is that Bad Girl comics weren’t an accident of taste. They were the culmination of decades of visual language, filtered through a market that rewarded excess.

Long before the 1990s flood, there were characters who laid the groundwork.

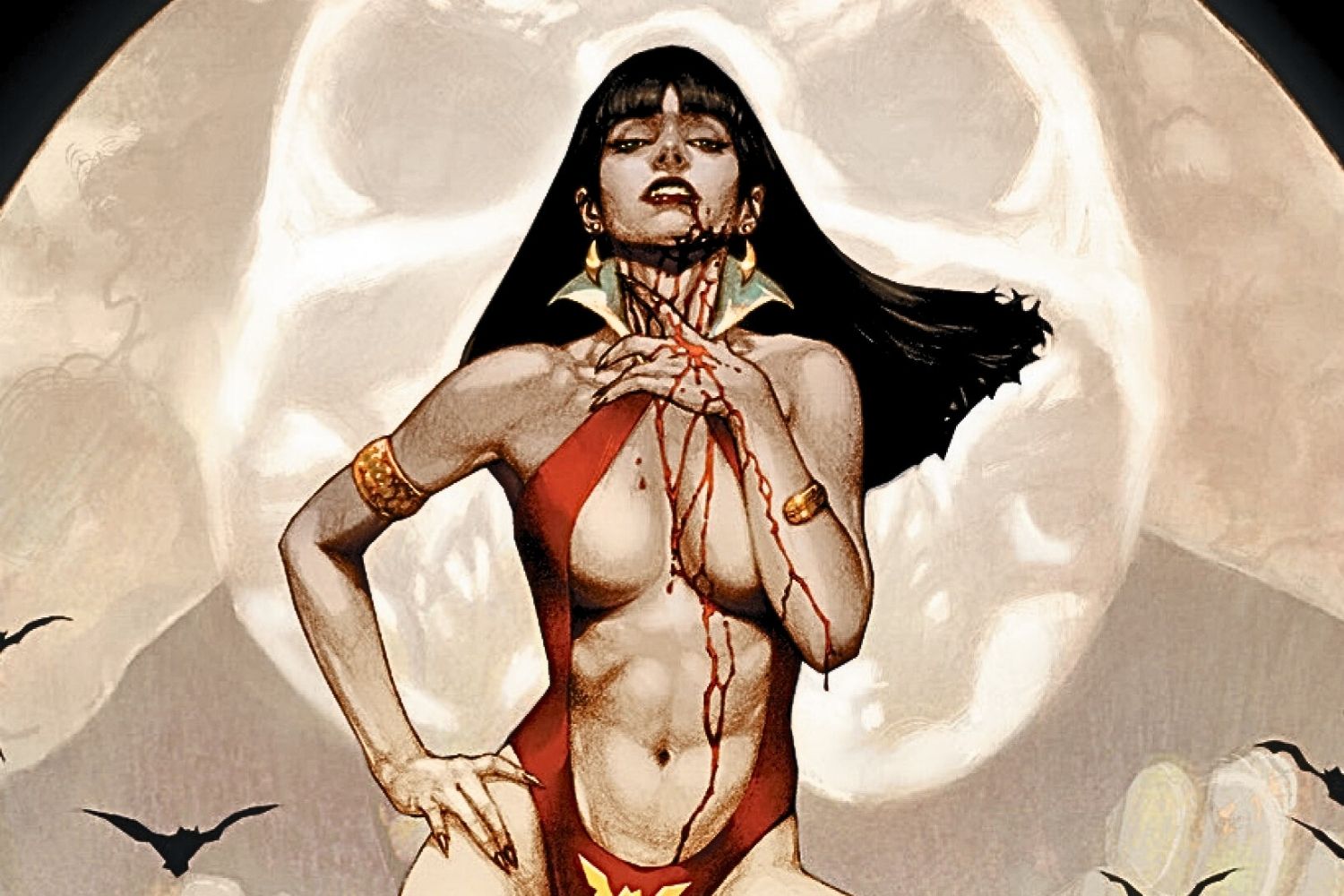

If you want a single character who bridges pulpy erotica and modern Bad Girl comics history, it’s Vampirella.

Introduced in 1969 by Warren Publishing, Vampirella was horror-host, vampire, and sex symbol rolled into one. Her costume was already doing work that later 90s books would simply exaggerate. More importantly, Vampirella proved that a female-led, sexually charged horror comic could sell—especially outside the traditional superhero mold.

When Harris Comics relaunched Vampirella in the early 1990s, it became one of the major catalysts for the Bad Girl resurgence. The timing was perfect. The audience was primed. And the market wanted characters that felt darker and sharper than mainstream Marvel and DC heroines.

Red Sonja’s chainmail bikini has launched a thousand arguments, but from a historical standpoint, she matters. Introduced in the 1970s, she established a template: savage warrior, minimal armor, complete agency. That combination echoes loudly in 90’s bad girl comics.

Frank Miller’s Elektra in the 1980s deserves special mention. While not a Bad Girl comic in the 90s sense, Elektra was violent, sexualized, morally ambiguous, and deadly. She proved that audiences could embrace a female character who was neither hero nor damsel—and that would matter a lot in the decade to come.

These characters didn’t belong to the Bad Girl boom, but they made it possible.

Check out our ranking guide for the top 50 female superheroes.

The bad girl comics origin story is inseparable from the early 1990s market conditions.

This was the era of:

In that environment, books like Evil Ernie and Lady Death were proof of concept.

Lady Death, in particular, became a cornerstone. She checked every box:

Once Lady Death worked, publishers followed. Fast.

You start seeing waves of similar titles from Chaos!, Image-adjacent studios, and smaller indie houses. Some had real creative energy. Others were clearly cash-ins. But all of them leaned into the same visual language.

That’s how trends work. Especially in the 1990s.

One of the biggest mistakes people make when discussing bad girl comics history is treating it as purely aesthetic. It wasn’t.

This was a direct market phenomenon.

Bad Girl comics thrived because:

Many of these books were ordered heavily at launch, then dropped quickly. That’s why so many issues show up today in near-mint condition—yet still have little value. High supply kills scarcity, no matter how flashy the cover is.

Understanding this market context is essential for collectors. Because value doesn’t follow nostalgia alone.

Here’s where we get practical.

If you’re flipping through longboxes and want to identify 90s Bad Girl comics quickly, look for these signs:

Many Bad Girl books came from:

Most copies found today are high grade, but not all are equal. Black covers show spine ticks easily. Foil and cardstock covers hide flaws poorly. Don’t assume NM without a close look.

This is where grading experience matters. A 9.8 on a low-print early issue is a completely different animal than a shiny 9.2 common book.

Explore this comic collector’s guide by Hovig.

Let’s be honest: most 90s Bad Girl comics are common.

But not all of them.

What still matters today?

Books connected to Lady Death, early Vampirella relaunches, and certain Chaos! titles still see collector interest, especially in certified high grade.

The trick is separating cultural importance from market saturation. A character can be influential and overprinted.

Here’s the part that often gets skipped.

Even after the Bad Girl boom collapsed in the late 1990s, its influence stuck around.

Mainstream publishers learned lessons, some good, some questionable:

But they also learned what not to repeat endlessly.

You can draw a straight line from Bad Girl comics to later characters who balanced sexuality with stronger narrative depth. The industry didn’t go backwards; it just recalibrated.

And that’s important. The 1990s weren’t a dead end. They were a testing ground.

From a grading and collecting standpoint, Bad Girl comics are fascinating.

They’re everywhere. But great copies are rarer than people think. Especially for books with heavy blacks, foils, or experimental materials.

When evaluating potential value:

We see these books come through grading submissions all the time. Most won’t ever spike. But a few, handled carefully and understood correctly, deserve a second look.

Bad Girl comics function as market artifacts from the peak of the direct-market experiment. Each issue reflects a moment when speed and visibility mattered more than restraint and understanding the bad girl comics origin gives collectors practical clarity. It explains why these books exist in such volume and why most survived in high grade.

Context protects you from noise. It replaces surface-level nostalgia with pattern recognition. When you know how the 1990s superhero comics boom shaped publishing decisions, the covers stop selling you. The data starts speaking instead.

For collectors, this knowledge changes how you hunt. You stop chasing gloss and start tracking first appearances, early relaunches, and quiet print runs that escaped mass ordering. Condition becomes a filter instead of a wish.

Bad Girl comics remain easy to find. Meaningful copies do not. The difference comes down to history, paper, and judgment. That is where disciplined collecting begins.